Winston

Lorenzo von Matterhorn

- Joined

- Jan 31, 2009

- Messages

- 9,560

- Reaction score

- 1,749

Autonomous Glider Ballooned to 10 km Altitude, Lands Safely 200 km Away

30 May 2018

https://hackaday.com/2018/05/30/autonomous-spaceplane-travels-to-10-km-lands-safely-200-km-away/

The goal of this project was to drop a glider from the edge of space using a high altitude weather balloon. The glider is entirely homemade and uses the opensource Pixhawk flight controller + a Raspberry Pi Zero to disconnect at the desired altitude and fly to a predetermined landing location. There is no direct radio contact with the aircraft, but we included a GPS tracker made for cars in case the glider didnt make it to the landing site.

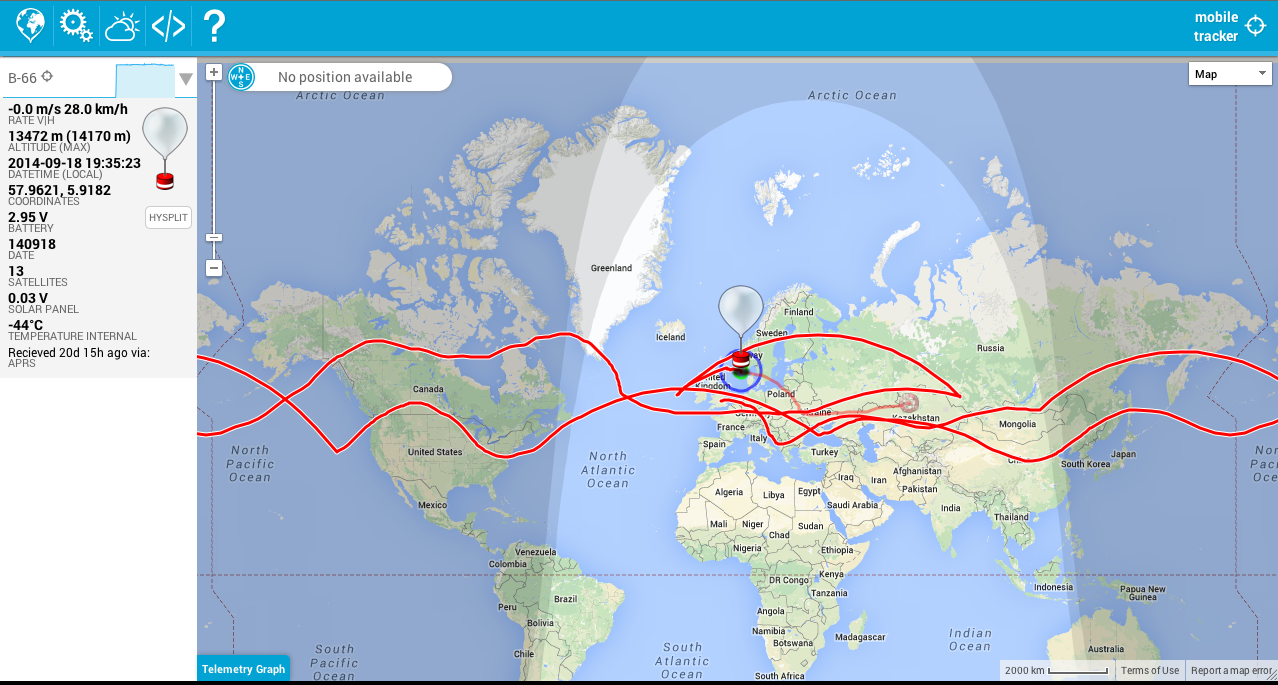

We tested the glider by first dropping it from a homemade quadcopter. This took 6 test-flights. Satisfied that everything was working properly, we prepared to launch the glider from the balloon. Although our target was 30km, we only had a few free days to launch, and on every day predictions showed that strong stratospheric winds would blow the glider hundreds of miles into the ocean if we launched from that height. We settled for a 10km launch altitude, and set the Pixhawk to land at a location within 20km of where the predictions estimated it would end up if it simply free-fell from the balloon.

We inflated the balloon, tied the glider to a long string to minimize swinging, and let it go. It was a two hour drive from the launch site to the landing location, and when we got there the glider was sitting on the ground roughly 10m from the target!

Max Altitude: 10.048km, 6.243mi

Max Speed: 95.5m/s, 212.5mph

Time Aloft: 2hrs 8min 18s

Dist Traveled: 195.95km, 121.76mi

THE GLIDER:

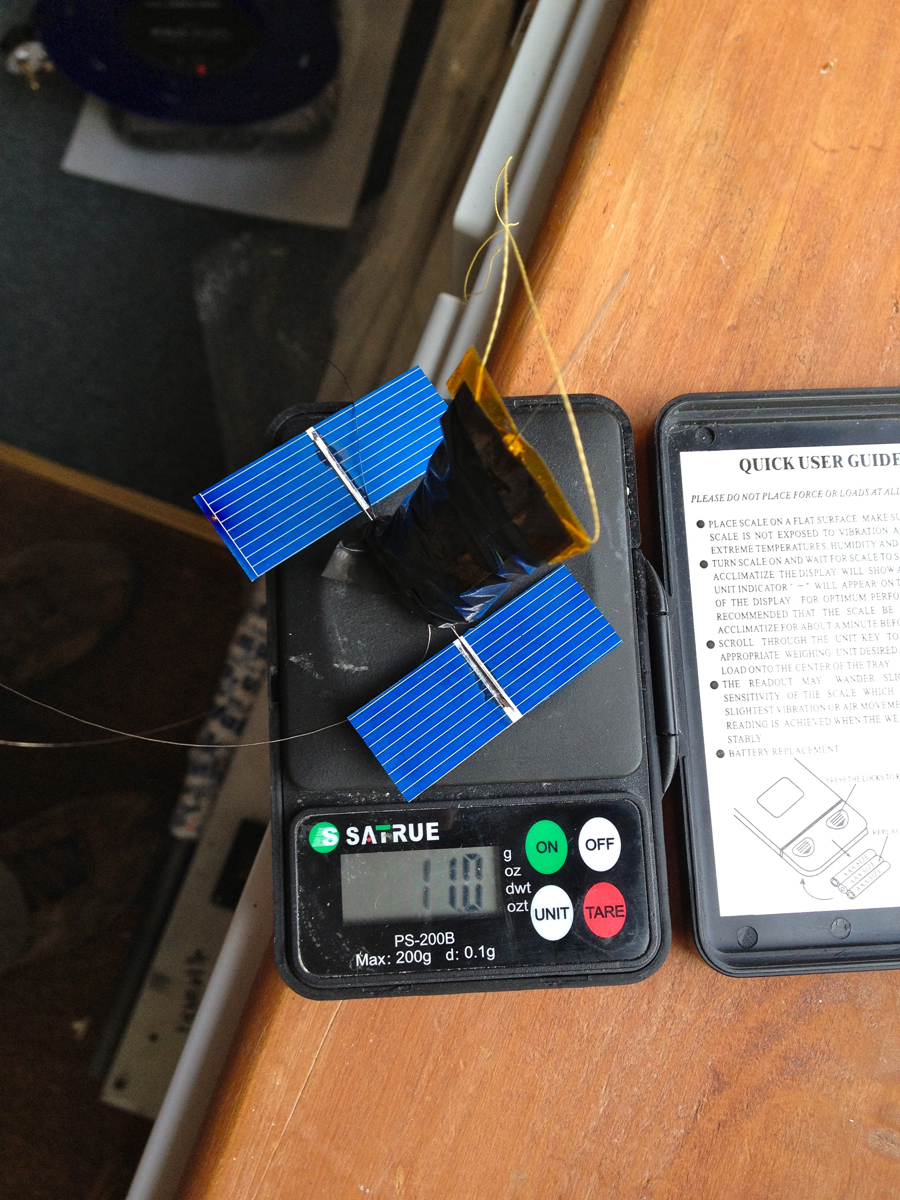

The glider is built from foamcore with coroplast for winglets and control surfaces, and laminated with colored tape for water-proofing. It carries two mobius cameras, two servos, a pixhawk flight controller with GPS, and a separate GPS/GSM tracker. Critically, all the electronics are inside the fuselage, which we packed with handwarmers and sealed shut before the flight to keep anything from freezing. Two 5200mAh 3s batteries provided more than enough power for a two hour flight (we were hoping to fly longer and higher). The takeoff weight was ~1300g.

THE FLIGHT CONTROL:

We used a Pixhawk for flight control. A Raspberry pi zero is connected to the pixhawk via USB and communicates with the Pixhawk using the Mavlink protocol. A simple python script on the Pi sets the flight mode on the Pixhawk to MANUAL on startup to prevent the servos from moving and wasting the battery during ascent. The script continuously checks the altitude, and when it reaches the target, triggers a solid state relay to burn a short piece of nickel-chromium wire, disconnecting the glider from the balloon. The script then sets the flight mode to AUTO, so the Pixhawk will direct the glider to a single target waypoint.

Source code: https://github.com/IzzyBrand/spaceplane

THE BALLOON:

The ballon is an old military surplus balloon I bought off ebay for $60. Not sure what the actual size was, there was little documentation. It came with a skirt which we cut off to save weight. We inflated it with half a K-tank of helium, though we probably could have gotten by with an S-tank. At launch, the balloon was generating a lift force of ~3000g. We used the https://habhub.org/ predictor to estimate the flight path and select a disconnect altitude of 10000m.

[video=youtube;q10gKcguXW0]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q10gKcguXW0[/video]

30 May 2018

https://hackaday.com/2018/05/30/autonomous-spaceplane-travels-to-10-km-lands-safely-200-km-away/

The goal of this project was to drop a glider from the edge of space using a high altitude weather balloon. The glider is entirely homemade and uses the opensource Pixhawk flight controller + a Raspberry Pi Zero to disconnect at the desired altitude and fly to a predetermined landing location. There is no direct radio contact with the aircraft, but we included a GPS tracker made for cars in case the glider didnt make it to the landing site.

We tested the glider by first dropping it from a homemade quadcopter. This took 6 test-flights. Satisfied that everything was working properly, we prepared to launch the glider from the balloon. Although our target was 30km, we only had a few free days to launch, and on every day predictions showed that strong stratospheric winds would blow the glider hundreds of miles into the ocean if we launched from that height. We settled for a 10km launch altitude, and set the Pixhawk to land at a location within 20km of where the predictions estimated it would end up if it simply free-fell from the balloon.

We inflated the balloon, tied the glider to a long string to minimize swinging, and let it go. It was a two hour drive from the launch site to the landing location, and when we got there the glider was sitting on the ground roughly 10m from the target!

Max Altitude: 10.048km, 6.243mi

Max Speed: 95.5m/s, 212.5mph

Time Aloft: 2hrs 8min 18s

Dist Traveled: 195.95km, 121.76mi

THE GLIDER:

The glider is built from foamcore with coroplast for winglets and control surfaces, and laminated with colored tape for water-proofing. It carries two mobius cameras, two servos, a pixhawk flight controller with GPS, and a separate GPS/GSM tracker. Critically, all the electronics are inside the fuselage, which we packed with handwarmers and sealed shut before the flight to keep anything from freezing. Two 5200mAh 3s batteries provided more than enough power for a two hour flight (we were hoping to fly longer and higher). The takeoff weight was ~1300g.

THE FLIGHT CONTROL:

We used a Pixhawk for flight control. A Raspberry pi zero is connected to the pixhawk via USB and communicates with the Pixhawk using the Mavlink protocol. A simple python script on the Pi sets the flight mode on the Pixhawk to MANUAL on startup to prevent the servos from moving and wasting the battery during ascent. The script continuously checks the altitude, and when it reaches the target, triggers a solid state relay to burn a short piece of nickel-chromium wire, disconnecting the glider from the balloon. The script then sets the flight mode to AUTO, so the Pixhawk will direct the glider to a single target waypoint.

Source code: https://github.com/IzzyBrand/spaceplane

THE BALLOON:

The ballon is an old military surplus balloon I bought off ebay for $60. Not sure what the actual size was, there was little documentation. It came with a skirt which we cut off to save weight. We inflated it with half a K-tank of helium, though we probably could have gotten by with an S-tank. At launch, the balloon was generating a lift force of ~3000g. We used the https://habhub.org/ predictor to estimate the flight path and select a disconnect altitude of 10000m.

[video=youtube;q10gKcguXW0]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q10gKcguXW0[/video]