Winston

Lorenzo von Matterhorn

- Joined

- Jan 31, 2009

- Messages

- 9,560

- Reaction score

- 1,749

Fourth Spy at Los Alamos Knew A-Bomb’s Inner Secrets

Historians recently uncovered another Soviet spy in the U.S. atomic bomb program. Fresh disclosures show he worked on the device’s explosive trigger.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/27/science/manhattan-project-nuclear-spy.html

Last fall, a pair of historians revealed that yet another Soviet spy, code named Godsend, had infiltrated the Los Alamos laboratory where the world’s first atom bomb was built. But they were unable to discern the secrets he gave Moscow or the nature of his work.

However, the lab recently declassified and released documents detailing the spy’s highly specialized employment and likely atomic thefts, potentially recasting a mundane espionage case as one of history’s most damaging.

It turns out that the spy, whose real name was Oscar Seborer, had an intimate understanding of the bomb’s inner workings. His knowledge most likely surpassed that of the three previously known Soviet spies at Los Alamos, and played a crucial role in Moscow’s ability to quickly replicate the complex device. In 1949, four years after the Americans tested the bomb, the Soviets detonated a knockoff, abruptly ending Washington’s monopoly on nuclear weapons.

“It’s fascinating,” Harvey Klehr, an author of the original paper, said in an interview. “We had no idea he was that important.”

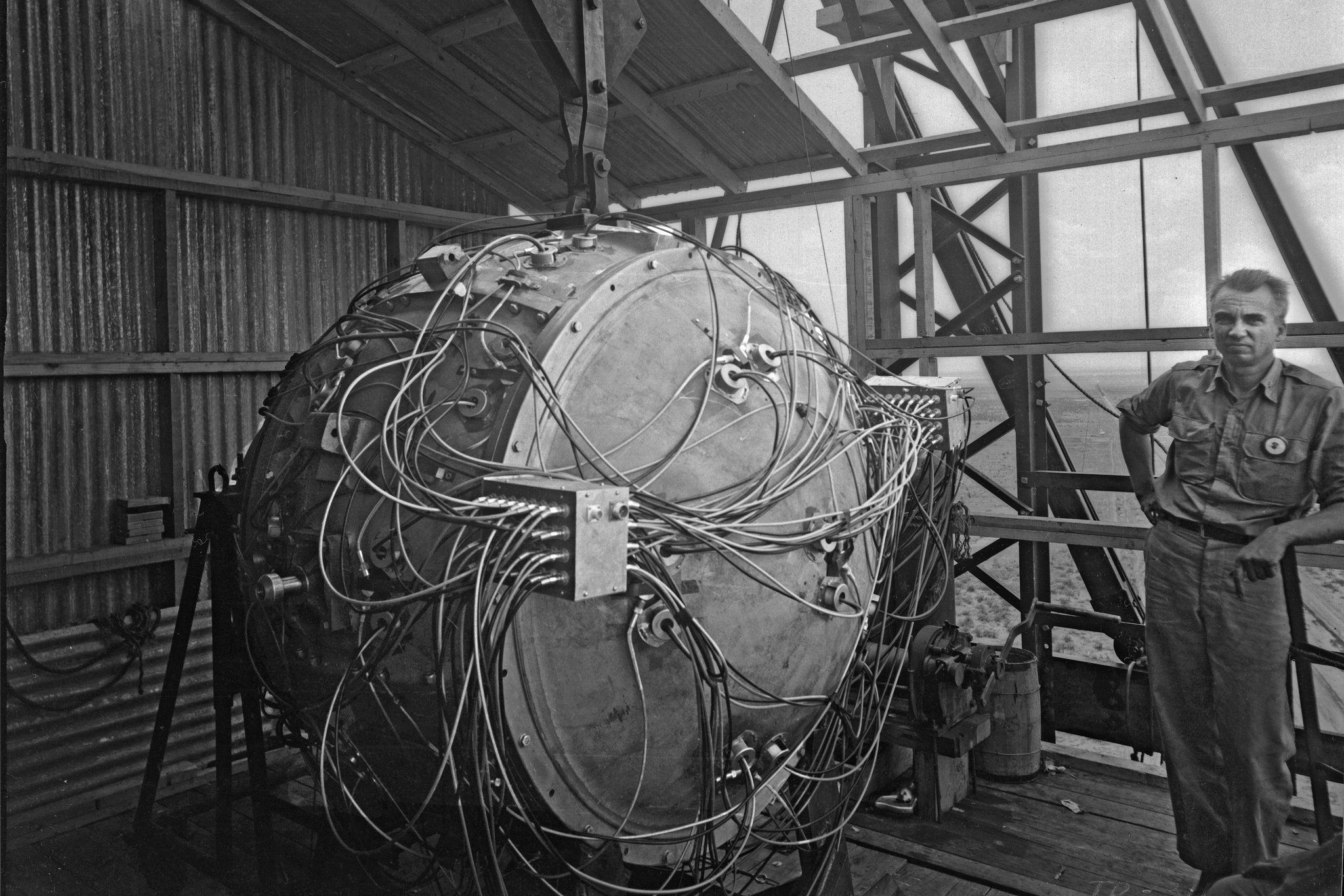

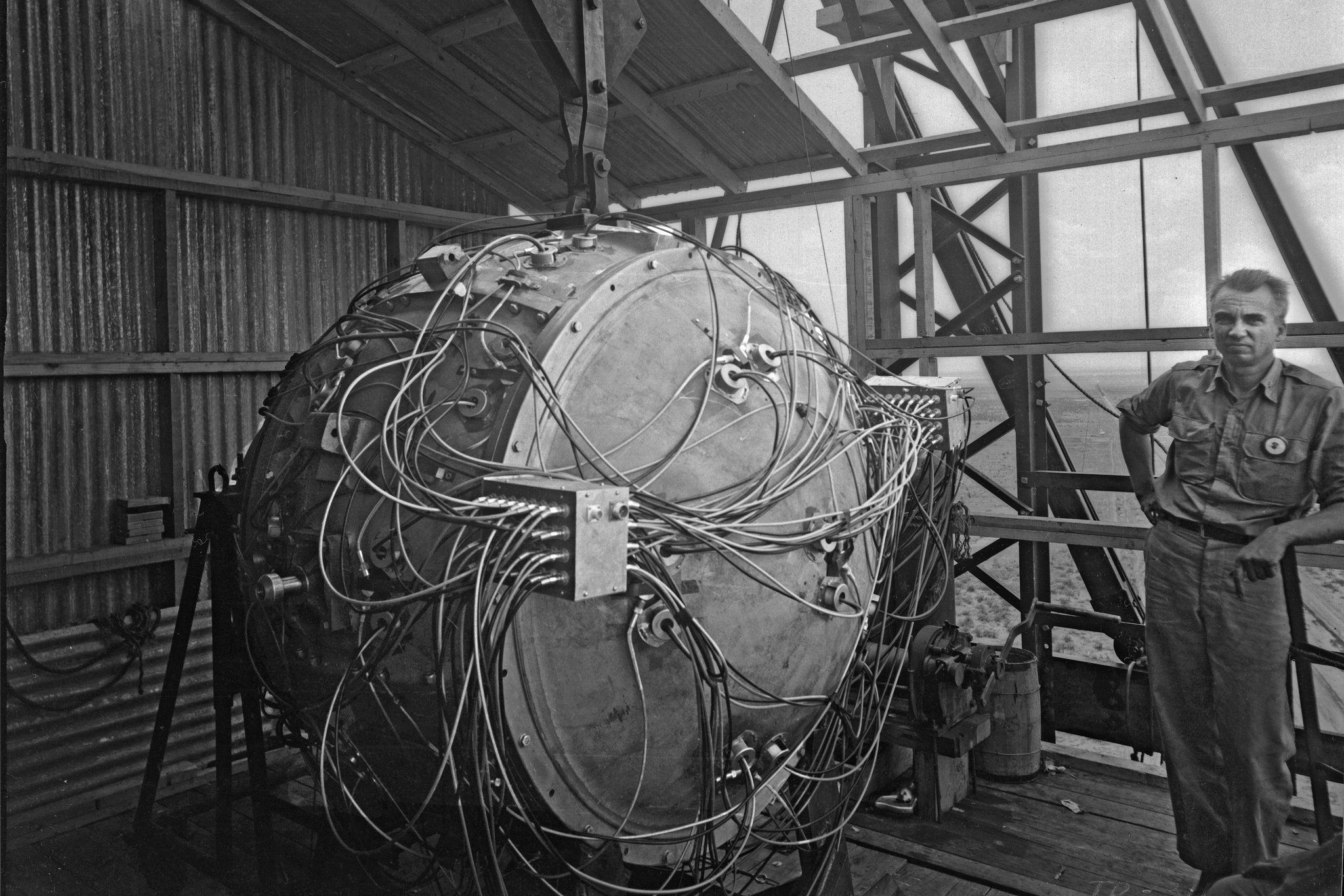

The documents from Los Alamos show that Mr. Seborer helped devise the bomb’s explosive trigger — in particular, the firing circuits for its detonators. The successful development of the daunting technology let Los Alamos significantly reduce the amount of costly fuel needed for atomic bombs and began a long trend of weapon miniaturization. The technology dominated the nuclear age, especially the design of small, lightweight missile warheads of enormous power.

[snip]

The new documents show that Mr. Seborer worked at the heart of the implosion effort. The unit that employed him, known as X-5, devised the firing circuits for the bomb’s 32 detonators, which ringed the device. To lessen the odds of electrical failures, each detonator was fitted with not just one but two firing cables, bringing the total to 64. Each conveyed a stiff jolt of electricity.

Glen McDuff, a Los Alamos scientist, once characterized the bomb’s firing circuits as “unbelievably complicated.”

A major challenge for the wartime designers was that the 32 firings had to be nearly simultaneous. If not, the crushing wave of spherical compression would be uneven and the bomb a dud. According to an official Los Alamos history, the designers learned belatedly of the need for a high “degree of simultaneity.”

Possible clues of Mr. Seborer’s espionage lurk in declassified Russian archives, Mr. Wellerstein of the Stevens Institute of Technology said in an interview. The documents show that Soviet scientists “spent a lot of time looking into the detonator-circuitry issue,” he said, and include a firing-circuit diagram that appears to have derived from spying.

The main appeal of implosion was that it drastically reduced the amount of bomb fuel needed. [Pu239 pits required the rapid compression of an implosion to avoid pre-detonation due to spontaneous neutrons emitted from unavoidable Pu240 content; more efficient use of fissile material was a side benefit which would be very useful even with U235 pits which didn't absolutely require implosion. - W] The dense metals were hard to obtain and far more valuable than gold. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were roughly equal in destructiveness — but fuel for the Nagasaki bomb weighed just 14 pounds — one-tenth the weight of the fuel for the Hiroshima bomb. The secret of implosion thus represented the future of atomic weaponry.

Slowly, nuclear experts say, bomb designers cut the plutonium fuel requirement from 14 pounds to about two pounds — a metal ball roughly the size of an orange. These tiny atomic bombs became enormously important in the Cold War, because their fiery blasts served as atomic matches to ignite the thermonuclear fuel of hydrogen bombs.

https://www.ambienteparco.it/pdf/fissionweapons.pdf

Historians recently uncovered another Soviet spy in the U.S. atomic bomb program. Fresh disclosures show he worked on the device’s explosive trigger.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/27/science/manhattan-project-nuclear-spy.html

Last fall, a pair of historians revealed that yet another Soviet spy, code named Godsend, had infiltrated the Los Alamos laboratory where the world’s first atom bomb was built. But they were unable to discern the secrets he gave Moscow or the nature of his work.

However, the lab recently declassified and released documents detailing the spy’s highly specialized employment and likely atomic thefts, potentially recasting a mundane espionage case as one of history’s most damaging.

It turns out that the spy, whose real name was Oscar Seborer, had an intimate understanding of the bomb’s inner workings. His knowledge most likely surpassed that of the three previously known Soviet spies at Los Alamos, and played a crucial role in Moscow’s ability to quickly replicate the complex device. In 1949, four years after the Americans tested the bomb, the Soviets detonated a knockoff, abruptly ending Washington’s monopoly on nuclear weapons.

“It’s fascinating,” Harvey Klehr, an author of the original paper, said in an interview. “We had no idea he was that important.”

The documents from Los Alamos show that Mr. Seborer helped devise the bomb’s explosive trigger — in particular, the firing circuits for its detonators. The successful development of the daunting technology let Los Alamos significantly reduce the amount of costly fuel needed for atomic bombs and began a long trend of weapon miniaturization. The technology dominated the nuclear age, especially the design of small, lightweight missile warheads of enormous power.

[snip]

The new documents show that Mr. Seborer worked at the heart of the implosion effort. The unit that employed him, known as X-5, devised the firing circuits for the bomb’s 32 detonators, which ringed the device. To lessen the odds of electrical failures, each detonator was fitted with not just one but two firing cables, bringing the total to 64. Each conveyed a stiff jolt of electricity.

Glen McDuff, a Los Alamos scientist, once characterized the bomb’s firing circuits as “unbelievably complicated.”

A major challenge for the wartime designers was that the 32 firings had to be nearly simultaneous. If not, the crushing wave of spherical compression would be uneven and the bomb a dud. According to an official Los Alamos history, the designers learned belatedly of the need for a high “degree of simultaneity.”

Possible clues of Mr. Seborer’s espionage lurk in declassified Russian archives, Mr. Wellerstein of the Stevens Institute of Technology said in an interview. The documents show that Soviet scientists “spent a lot of time looking into the detonator-circuitry issue,” he said, and include a firing-circuit diagram that appears to have derived from spying.

The main appeal of implosion was that it drastically reduced the amount of bomb fuel needed. [Pu239 pits required the rapid compression of an implosion to avoid pre-detonation due to spontaneous neutrons emitted from unavoidable Pu240 content; more efficient use of fissile material was a side benefit which would be very useful even with U235 pits which didn't absolutely require implosion. - W] The dense metals were hard to obtain and far more valuable than gold. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were roughly equal in destructiveness — but fuel for the Nagasaki bomb weighed just 14 pounds — one-tenth the weight of the fuel for the Hiroshima bomb. The secret of implosion thus represented the future of atomic weaponry.

Slowly, nuclear experts say, bomb designers cut the plutonium fuel requirement from 14 pounds to about two pounds — a metal ball roughly the size of an orange. These tiny atomic bombs became enormously important in the Cold War, because their fiery blasts served as atomic matches to ignite the thermonuclear fuel of hydrogen bombs.

https://www.ambienteparco.it/pdf/fissionweapons.pdf